From the Northern Whig, 4 July 1879:

“Today, about one o’clock, the glass dome, with heavy leaden ventilator in the centre of the Consultation Room, adjoining the Library in the Four Courts, fell in with a great smash, strewing the floor beneath with broken glass and smashed sashes. The ventilator, three feet high and more than one hundredweight,lay with the side battered in. the room is small, and fortunately at the moment of the accident there was no one under the glass roof, but at the desks lining the walls more than a dozen lawyers and solicitors were seated… None were injured, but all were startled by the occurrence, which took place without any preliminary warning.

The instant before the roof fell, Mr Justice Barry and the Attorney-General were standing in the room. They had just gone into the library when the mishap took place. It turned out on examination that the sash was rotten, and unable to sustain the weight of the leaden ventilator fastened into the centre, and the whole structure, being loosened by the high wind, came down. It is not known whether the Board of Works, who have charge of the Four Courts and buildings, or the Library, are in default in connection with the state of the roof.”

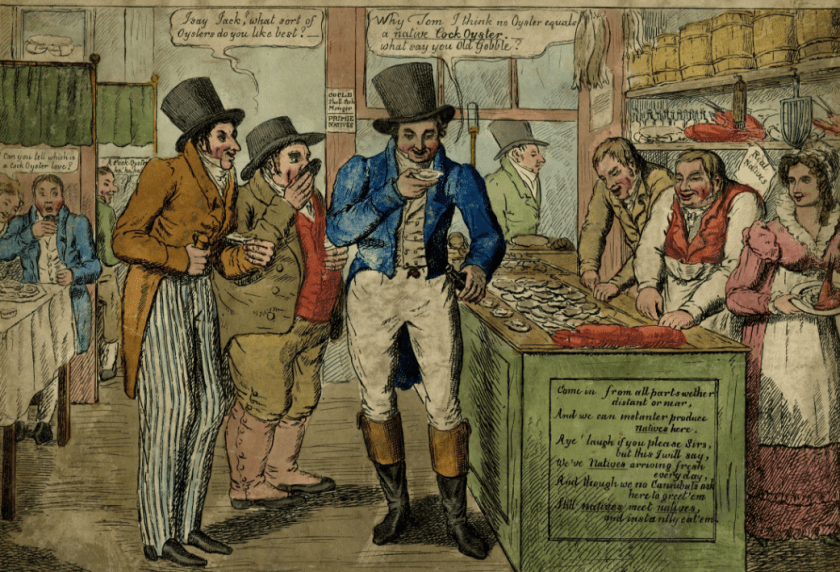

The Attorney-General, Edward Gibson QC, and the judge, Mr Justice Barry, face one another left to right above under a sketch of the first Law Library. The ill-fated glass-domed consultation room nestles just above the crown of Mr Justice Barry’s hat.

No one wanted to accept responsibility for the recently installed ventilator. The Board of Works said that matters within the Law Library were matters for the Benchers; the Benchers issued, through their architect, a statement that they had had nothing whatsoever to do with its installation.

The first Law Library appears to have been particularly unlucky with regard to roof collapses; read about an earlier one here.

The mystery of what one newspaper described as ‘the wandering ventilator’ continues to this day!

Picture Credit: (bottom left image) (bottom right image)